Introduction

Table of Contents

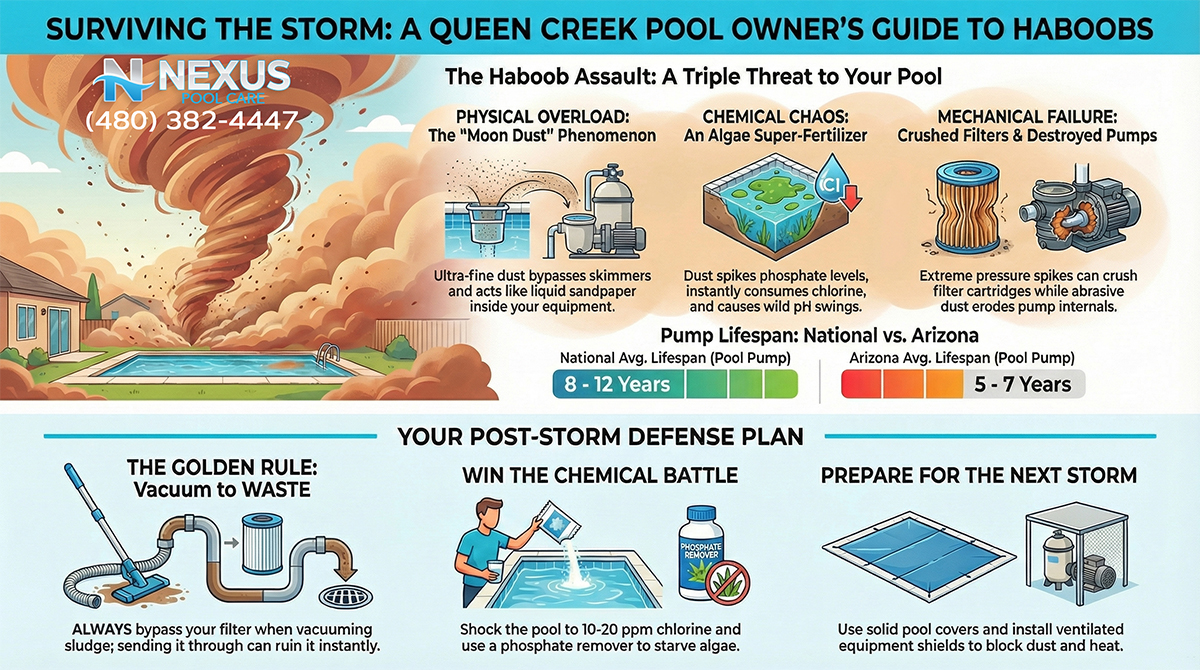

ToggleIn the rapidly developing municipalities of Queen Creek and San Tan Valley, Arizona, the residential swimming pool is not merely a lifestyle amenity; it is a complex hydraulic system engaged in a perpetual battle against a hostile aeolian environment. While the intense solar radiation and high ambient temperatures of the Sonoran Desert present consistent operational challenges, it is the acute, violent onset of the “haboob”—a massive, convective dust storm—that poses the single greatest threat to aquatic infrastructure. For stakeholders in this region, ranging from residential homeowners to commercial facility managers, understanding the interaction between these meteorological events and pool filtration systems is critical. It is a matter of preserving capital assets that are susceptible to catastrophic failure when subjected to the mechanical and chemical shock loads characteristic of these storms.

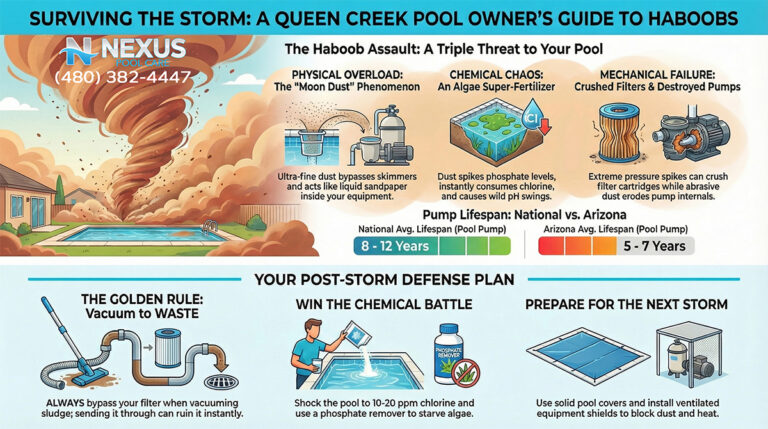

The term “haboob,” derived from the Arabic word for “blasting” or “drifting,” refers to an atmospheric gravity current generated by the collapse of a thunderstorm. In the American Southwest, and particularly in the agricultural lowlands of Pinal and Maricopa Counties, these events manifest as towering walls of dust that can exceed 5,000 feet in height and span up to 100 miles in width. Unlike a standard windy day, a haboob creates a unique debris profile. The particulate matter lofted by the storm is not uniform; it is a heterogeneous mixture of the local “Queencreek” soil series—a sandy loam rich in fine silicates—combined with anthropogenic contaminants, agricultural byproducts, and biological agents.

When this suspension interacts with a swimming pool, the result is a multi-phase system failure. The immediate visual consequence—turbid, “chocolate milk” water—masks a cascade of microscopic and mechanical damages occurring within the filtration and circulation equipment. The massive influx of silica acts as an abrasive, eroding pump impellers and scoring mechanical seals. The introduction of phosphates and nitrates from surrounding farmland chemically destabilizes the water, creating a nutrient-rich broth for algae that can overwhelm sanitizers in hours. Simultaneously, the hydraulic resistance across filter media spikes rapidly, leading to crushed cartridges, ruptured grids, and overheated motors.

This report offers an exhaustive technical analysis of these phenomena. It dissects the physics of debris loading, the chemistry of storm-induced contamination, and the mechanical wear patterns observed in pumps and filters operating in the Queen Creek basin. Furthermore, it outlines rigorous, engineering-grade protocols for immediate recovery and long-term mitigation, moving beyond generic advice to provide a blueprint for infrastructure resilience in one of North America’s most demanding aquatic environments.

Section 1: What Happens to Your Pool During a Dust Storm

The collision between a haboob and a swimming pool is a study in fluid dynamics and saturation mechanics. A pool, by design, is a large, open-topped vessel that functions as a sediment trap. When wind velocities drop following the passage of the storm front, the suspension of dust and debris settles into the water column, initiating a sequence of physical and chemical events that threaten the viability of the entire circulation system.

Heavy Debris Load and Sedimentation Physics

The defining characteristic of a Queen Creek haboob is the sheer mass of material deposited per square foot of surface area. Research into particulate matter concentrations (PM10) during these events indicates spikes reaching 9,983 µg/m³, an order of magnitude higher than standard background levels. This material is not merely dust; it is a complex aggregate sorted by wind velocity.

The “Moon Dust” Phenomenon and Particle Sizing

Residents often refer to the post-storm residue as “moon dust” due to its ultra-fine texture and cohesive properties. This silt consists largely of particles smaller than 10 microns (PM10) and even smaller fractions (PM2.5) that remain suspended in the atmosphere long after the heavy sand has settled. In the context of pool filtration, this particle size distribution is particularly problematic. Standard skimmer baskets, designed to trap leaves and insects with dimensions in the centimeter range, are completely transparent to this fine silt.

As the dust settles, it follows Stokes’ Law, which dictates that larger, denser silica particles settle to the pool floor rapidly, creating sludge banks. However, the finer clays and organic colloids remain suspended, causing extreme turbidity that can reduce visibility to near zero. This suspension poses a severe threat to the main drain of the pool. If the pump is active during or immediately after the storm, this high-concentration slurry is drawn directly into the suction line. Unlike leaves, which can block flow, this slurry passes through the pump strainer basket and enters the pump volute, where it acts as a grinding paste against the impeller and seal faces before being forced into the filter media.

The Agricultural Soil Matrix

The specific geography of Queen Creek exacerbates this issue. The local soil, taxonomically classified as the Queencreek Series, is a sandy-skeletal, mixed, thermic Typic Torrifluvent. This soil formed from mixed stream alluvium on flood plains, meaning it is naturally rich in variable-sized sediments ranging from fine gravel to loamy sand. When lofted by 60 mph winds, this soil carries with it the legacy of the region’s agricultural history. The dust is not sterile mineral matter; it is laden with dried organic chaff, pollen, and microscopic debris from livestock and crop fields. This organic fraction adds a “biological load” to the physical sediment load, creating a sludge that is often sticky and resistant to simple backwashing.

Chemical Dilution and Biological Instability

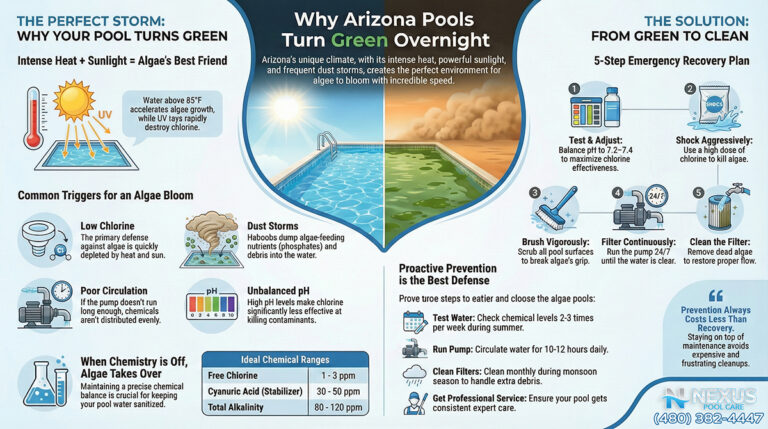

While the physical debris is the most visible impact, the chemical destabilization of the pool water is often the more expensive consequence. A haboob is rarely a dry event; it is often the outflow of a convective thunderstorm that may subsequently dump rain on the region. This creates a “double tap” of chemical alteration: contamination from the dust followed by dilution from the rain.

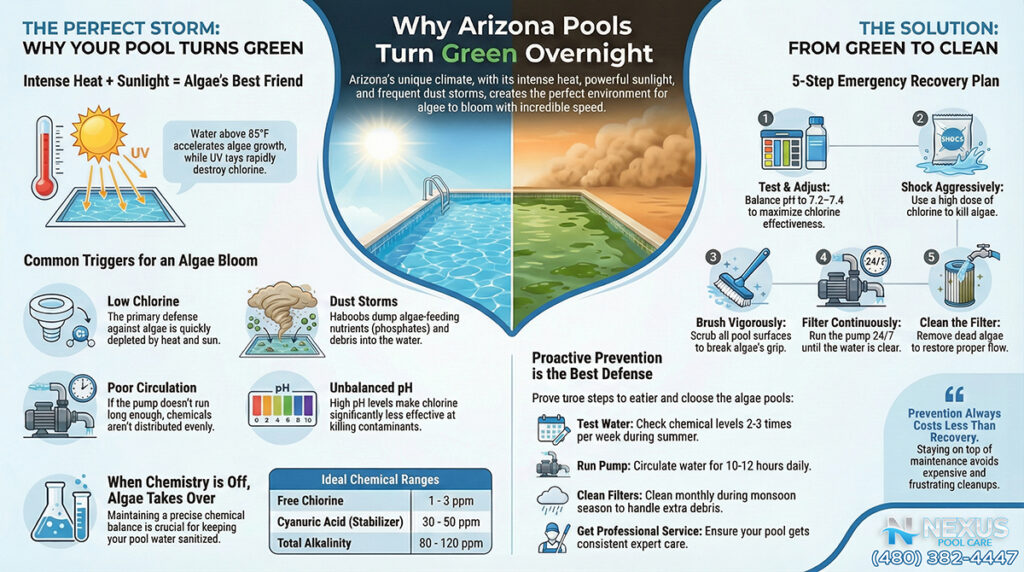

The Phosphate and Nitrate Injection

Queen Creek’s proximity to active farmland means that the dust carried by haboobs is frequently contaminated with fertilizers. Phosphates and nitrates are the primary nutrients for plant growth, and when introduced into a swimming pool, they act as a hyper-accelerant for algae blooms. Phosphates are the limiting nutrient in most pools; when levels remain low, algae struggles to grow even if chlorine dips. However, a single dust storm can raise phosphate levels from a healthy near-zero to over 3,000 parts per billion (ppb) overnight.

Nitrates present a more insidious problem. Unlike phosphates, which can be removed with chemical sequestering agents (like Lanthanum chloride), nitrates are difficult to remove from water without reverse osmosis or draining the pool. High nitrate levels “lock” the chlorine, making it significantly less effective at sanitation. This creates a scenario where a pool owner may test their water and see a standard chlorine reading, yet still experience a massive algae bloom because the chlorine is overwhelmed by the nutrient load.

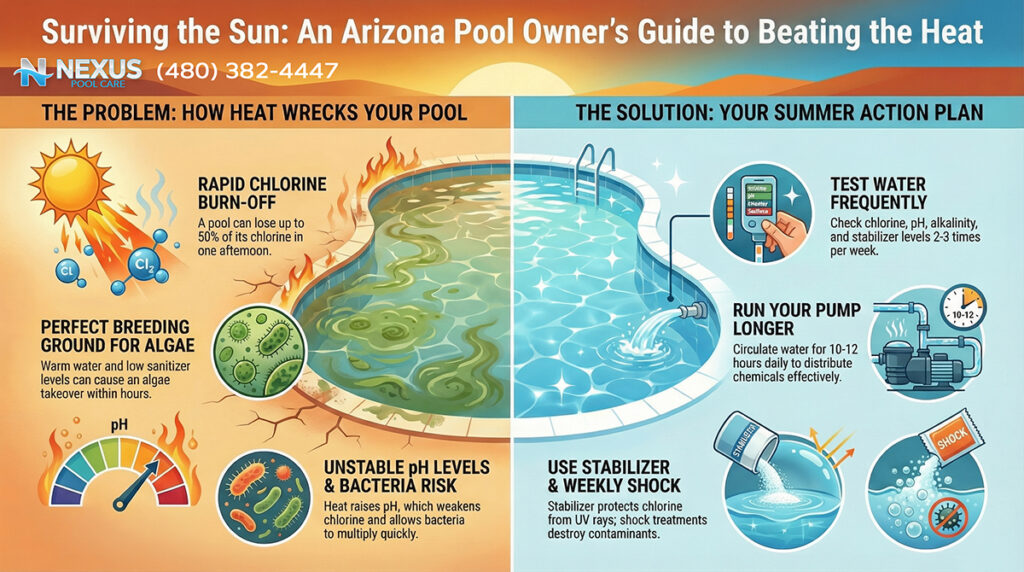

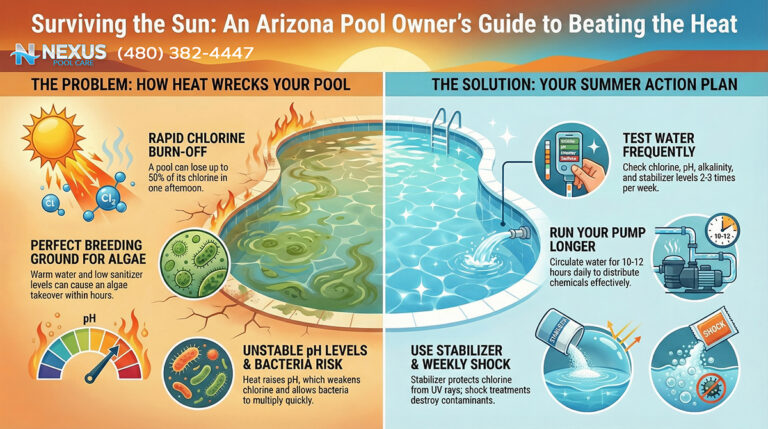

Chlorine Demand and pH Chaos

The influx of organic matter—pollen, leaf litter, and biological dust—creates an immediate and massive “chlorine demand.” Chlorine is an oxidizer; its primary job is to burn up organic contaminants. When pounds of organic dust enter the water, the free chlorine residual is consumed rapidly as it attempts to oxidize this load. It is common for a pool with a robust 3-5 ppm (parts per million) chlorine level to drop to 0 ppm within hours of a storm. Once the chlorine is depleted, the biological agents in the dust, including algae spores and bacteria, reproduce unchecked.

Simultaneously, the pH of the water undergoes violent fluctuations. Rainwater is naturally acidic, with a pH typically between 5.0 and 5.5 due to atmospheric carbon dioxide forming weak carbonic acid. Conversely, the desert dust in Arizona is highly alkaline, often containing calcium carbonate (caliche) with a pH well above 8.0. Depending on the ratio of rain to dust, the pool’s pH can swing wildly. A drop in pH (acidic) can corrode heater exchangers and pump seals, while a spike in pH (alkaline) causes dissolved calcium to precipitate out of the water, leading to scaling on tile lines and turning the water cloudy. This scaling is further aggravated by the naturally hard water of the region, where calcium hardness levels often exceed 250 ppm.

Filter Overload and Hydraulic Throttling

The final and most mechanical consequence of the storm is the overload of the filtration medium. Every filter—whether sand, cartridge, or diatomaceous earth (DE)—operates on the principle of trapping particles in a porous media. This media has a finite surface area and a finite “dirt holding capacity.”

The Pressure Spike

Under normal operating conditions, a filter accumulates debris slowly over weeks, resulting in a gradual rise in internal pressure (typically 1 PSI per week). A haboob compresses months of debris loading into a single hour. This results in a rapid, vertical spike in filter pressure, often exceeding the clean starting pressure by 20-30 PSI if the pump is left running.

Hydraulic Consequence

This pressure spike has immediate hydraulic consequences. As the filter media blinds off with dust, the resistance to flow increases drastically. On a standard centrifugal pool pump curve, this pushes the operation point to the far left—high head, low flow.

- Circulation Failure: As flow drops, the turnover rate of the pool decreases. Chemicals added to the pool are not mixed effectively, leading to localized zones of unsanitized water where algae can take hold. Skimmers stop functioning because there is insufficient suction to pull floating debris into the basket, allowing it to sink.

- Bypass and Bleed-Through: In sand filters, excessive pressure can force fine dust to push all the way through the sand bed and return to the pool, creating a cycle where the filter is essentially ineffective. In cartridge filters, extreme pressure can collapse the center cores of the cartridge elements, physically crushing them and rendering them useless.

The impact of a haboob is a comprehensive assault on the pool’s equilibrium. The physical weight of the sediment stresses the cleaning systems; the chemical composition of the dust strips the water of its sanitary protection; and the hydraulic resistance generated by the clog threatens the mechanical integrity of the pump and filter. Understanding this triad of failure modes—physical, chemical, and hydraulic—is the prerequisite for effective remediation.

Section 2: How Dust Damages Filters and Pumps

The damage inflicted by haboob dust is not merely a matter of clogging; it involves abrasive wear, structural deformation, and material contamination that varies significantly depending on the type of equipment installed. In Queen Creek, where equipment runs year-round in high ambient temperatures, the margin for error is slim. The interaction between the specific geology of the dust (silica, clay) and the mechanics of pool equipment leads to distinct failure patterns.

Clogged Cartridges: Structural and Functional Failure

Cartridge filters are widely used in Arizona due to water conservation mandates, as they do not require backwashing. These filters typically utilize a spun-bonded polyester fabric (Reemay) arranged in pleats to maximize surface area. While effective at trapping particles in the 10-20 micron range, they are uniquely vulnerable to the “cementing” nature of haboob dust.

Depth Loading vs. Surface Loading

Standard pool debris, like leaves or dead algae, typically loads on the surface of the cartridge pleats. Haboob dust, however, consists of sub-micron fines that penetrate deep into the fibrous matrix of the polyester. This “depth loading” is difficult to reverse. If the dust contains high levels of calcium carbonate (common in desert soils) and the cartridge is allowed to dry out, the dust effectively turns into cement within the fibers. Once this occurs, even aggressive acid washing may fail to restore flow, as the acid can set the silica-organic matrix permanently into the fabric.

Structural Collapse

The most catastrophic failure mode for cartridge filters during a storm is core collapse. As the pleats become blinded by dust, the differential pressure—the difference in pressure between the outside of the cartridge (dirty side) and the inside core (clean side)—increases. If this differential exceeds the structural rating of the plastic core (often around 50 PSI), the cartridge will implode. This phenomenon, known as “crushing,” creates a crumpled, soda-can appearance and breaks the seal between the cartridge and the manifold, allowing dirty water to bypass filtration entirely.

Band Breakage

Cartridges rely on horizontal bands to keep the pleats evenly spaced. The weight of the wet, heavy mud accumulated during a haboob creates immense drag on the fabric. This stress often snaps the bands. Without bands, the pleats collapse against one another, effectively reducing the filter’s surface area by 50% or more. This accelerates the clogging rate and makes the cartridge impossible to clean effectively, as a hose stream cannot penetrate the folded-over pleats.

Sand and DE Contamination

While cartridge filters suffer from structural failure, sand and DE filters suffer from media contamination that fundamentally alters their filtration characteristics.

Sand Filters: Channeling and Mud-Balling

Sand filters use #20 silica sand (0.45–0.55 mm diameter) to trap debris. The physics of sand filtration relies on the rough edges of the sand grains to snag particles.

- Mud-Balling: When the heavy, organic-laden silt from a haboob enters a sand filter, it typically accumulates in the top few inches of the sand bed. If this layer is not backwashed immediately and thoroughly, the silt mixes with the biological oils and glues the sand grains together into “mud balls.” These clumps are impermeable. Water, following the path of least resistance, channels around these mud balls rather than through the sand. This channeling allows dirty water to pass untreated through the filter, resulting in a pool that remains cloudy regardless of how long the pump runs.

- Media Glazing: Over time, the high velocity of abrasive silica dust passing through the filter polishes the sharp edges of the filter sand, making the grains round and smooth. This “glazing” reduces the sand’s ability to trap fine particles, necessitating media replacement.18

Diatomaceous Earth (DE) Filters: The Bridging Effect

DE filters are capable of filtering down to 2-5 microns, offering the best clarity. However, this precision makes them the most fragile in a storm.

- Rapid Bridging: DE grids are covered in a fabric mesh coated with DE powder. The ultra-fine silt from a haboob can coat the DE cake so rapidly that it forms an impermeable “bridge” across the grid elements. This causes pressure to spike much faster than in sand or cartridge filters.

- Internal Damage: The plastic grids inside a DE tank are lightweight. The hydrostatic pressure generated by a blinded DE cake can be sufficient to crush the internal manifold or tear the fabric mesh. Once the fabric tears, DE powder (a white, chalky substance) shoots back into the pool, creating a new mess that settles on the floor.

Pump Strain and Mechanical Degradation

The pool pump is the component most likely to suffer permanent, expensive damage from a haboob. This damage is threefold: abrasive, thermal, and tribological (seal wear).

Impeller Erosion (The Sandblaster Effect)

The dust in Queen Creek is largely composed of silica (quartz), which has a Mohs hardness of 7. When water laden with this suspended grit passes through the pump, it acts as a liquid sandpaper.

- Vane Wear: The impeller vanes, which spin at 3,450 RPM, are bombarded by these particles. This erosion alters the geometry of the vanes, reducing their ability to move water. Over time, this manifests as a permanent loss of flow and pressure, even when the filter is clean.

- Volute Scouring: The grit also scours the inside of the pump housing (volute), increasing the clearance between the impeller and the housing. This “slip” reduces hydraulic efficiency, forcing the motor to work harder to move less water.

Mechanical Seal Failure

The mechanical seal is a precise component consisting of a ceramic stationary face and a carbon rotating face, polished to a flatness measured in light bands. It prevents water from leaking along the motor shaft.

- Face Scoring: Fine haboob dust can migrate between these polished faces. The grit scores the carbon face, creating a leak path. Once a seal begins to leak, chlorinated water sprays onto the motor bearings, leading to bearing corrosion and the characteristic “screaming” noise of a failing motor.

- Thermal Shock: If the skimmer baskets clog with storm debris (leaves, plastic bags), the pump is starved of water. The friction of the spinning seal generates immense heat—enough to melt the plastic impeller and the seal seat—within minutes. This “dry run” scenario is a common cause of pump death immediately following a storm.

Motor Overheating

Pool motors are air-cooled and typically rated to operate in ambient temperatures up to 40°C or 50°C (104°F – 122°F). In a Queen Creek summer, ambient temperatures often approach 115°F.

- Airflow Blockage: Dust storms coat the ventilation grates of the motor with a thick layer of insulating dust. This restricts the airflow required to cool the windings.

- Thermal Compounding: The combination of high ambient heat, insulating dust, and increased load from a clogged filter pushes the internal motor temperature beyond the insulation class rating (Class B or F). This eventually causes the insulation on the copper windings to melt, resulting in an electrical short and motor failure.

The interaction between haboob dust and pool equipment is a destructive cycle. The dust clogs the filter, which raises pressure and lowers flow; the lower flow causes the pump to overheat; the abrasive dust wears out the pump internals; and the chemical load attacks the system from within. Breaking this cycle requires immediate and specific intervention.

Section 3: Immediate Post-Storm Pool Care Steps

Recovery from a haboob is a triage operation. The order in which maintenance tasks are performed is critical; performing them out of sequence (e.g., filtering before removing bulk debris) can destroy equipment. The goal is to remove the solid load from the pool with minimal impact on the filtration system, a process that often requires bypassing standard operating modes.

Skimming and Surface Management

Objective: Prevent suction blockage and sinkage of organic debris.

Before any pump is engaged or any valve turned, the surface of the pool must be cleared. The wind associated with haboobs often brings heavier organic debris—leaves, palm fronds, oleander flowers—that settles on the surface.

- The Deep Net Protocol: Standard flat skimmer nets are ineffective for the volume of debris generated by a storm. A “deep bag” leaf rake is essential to scoop large volumes of debris without creating a wake that pushes it out of the net.

- Basket Triage: The skimmer baskets and the pump strainer basket must be emptied immediately. In the aftermath of a storm, these baskets can fill in minutes. A clogged pump basket is the primary cause of loss of prime, which leads to the dry-running pump failures described in Section 2.

- Do Not Drain: Despite the water resembling “chocolate milk,” pool owners must resist the urge to drain the pool entirely. Monsoon storms often raise the local water table. Draining a pool when the groundwater is high creates hydrostatic pressure that can float the pool shell out of the ground, cracking the concrete and destroying plumbing.

Vacuuming: The “Vacuum to Waste” Imperative

Objective: Remove sediment without passing it through the filter media.

The single most important rule of haboob recovery is: Do not vacuum haboob sludge into a cartridge filter. The volume of silt is sufficient to ruin a set of cartridges in a single session. The debris must be removed from the pool without ever touching the filter media.

Method A: Multiport Valve Systems (Sand/DE)

For pools equipped with Sand or DE filters, a multiport valve typically controls the flow.

- Water Level: Overfill the pool by 2-4 inches using a garden hose, as this process consumes water rapidly.

- Valve Setting: With the pump off, switch the valve to the “WASTE” position. This directs water from the pump, out the backwash line, and onto the ground/drain, bypassing the filter tank entirely.

- Execution: Vacuum quickly, focusing on the heaviest sludge deposits. Stop if the water level drops below the skimmer to prevent the pump from sucking air.

Method B: Cartridge Systems (The Queen Creek Challenge)

Most newer pools in Queen Creek utilize large single-cartridge filters with no multiport valve, making “vacuum to waste” difficult.

- Trash Pump Solution: The most effective method is to use an external “trash pump” (gas or electric). These pumps are designed to pass solids up to 1 inch in diameter. By connecting a vacuum hose directly to the intake of a trash pump, the homeowner can vacuum the pool completely independent of the pool’s plumbing, discharging the sludge into a sewer cleanout or landscape drainage. Safety Note: Gas-powered pumps must never be used indoors or in enclosed spaces due to carbon monoxide.

- Plumbing Modification: A proactive strategy involves installing a 3-way diverter valve between the pump and the filter. This allows the user to manually divert water out a waste line before it enters the filter. This requires cutting the PVC pipe, priming, and gluing a valve in place, a modification best done before storm season.

- The Drain Plug Hack: In an emergency, if no other option exists, the drain plug at the bottom of the filter canister can be removed. If the filter has a threaded outlet, a hose adapter can be installed to drain water while the pump runs. However, the cartridges should be removed from the tank during this process to prevent them from clogging.

Brushing and Suspension

Objective: Mobilize fine dust for filtration.

Once the bulk sediment is removed via the waste line, a fine layer of dust will remain on the walls, steps, and floor. This dust is often too fine to vacuum effectively without losing too much water.

- Suspension: Brush the entire pool aggressively, starting from the shallow end and working toward the main drain. The goal is to make the water cloudy. This suspends the particles in the water column, allowing the filtration system (now safe to use since the bulk mud is gone) to trap them.

- Algae Disruption: Brushing also serves to disrupt the protective biofilm of any algae that may have started to colonize the porous plaster surface due to the phosphate influx.

Filter Cleaning and Recovery

Objective: Restore hydraulic flow and remove trapped contaminants.

After the pool has been cleared, the filter will be heavily loaded and require thorough cleaning. The cleaning protocol depends on the filter type and the nature of the debris.

Cartridge Recovery Protocol

- Rinse: Remove cartridges and rinse with a high-pressure nozzle at a 45-degree angle, working from top to bottom. This prevents driving dirt deeper into the pleats.

- Degrease (Crucial Step): Do not skip this. The agricultural dust in Queen Creek often contains oils and pesticides. Soak the cartridges in a solution of Trisodium Phosphate (TSP) or a dedicated filter cleaner enzyme. This breaks down the oily binder holding the dirt in the fabric.

- Acid Wash (Conditional): Only after degreasing, if calcium scaling is visible, soak in a weak muriatic acid solution (1:20 ratio). Warning: Acid washing a cartridge that has not been degreased will permanently lock the oils into the fabric, ruining the filter.

- Replacement Indicators: If the bands are snapped, the pleats are flattened, or the core is cracked, the cartridge must be replaced. A compromised cartridge will allow dirt to bypass, damaging the pump and clouding the water.

DE Filter Recovery

- Backwash: Run a thorough backwash cycle until the sight glass is clear.

- Disassembly: Following a major haboob, backwashing is rarely sufficient to remove the caked sludge between the grids. The filter must be disassembled, and the grid pack manually hosed off. Inspect the grids for tears in the fabric, which indicate the need for replacement.

- Recharge: Reassemble and coat with fresh DE powder immediately to prevent raw dirt from embedding in the grid fabric.

Chemical Stabilization

Objective: Neutralize organic load and prevent algal bloom.

With the physical debris removed, the water chemistry must be aggressively corrected.

- Superchlorination: The pool must be “shocked” to a chlorine level of 10-20 ppm to satisfy the chlorine demand created by the organic dust. This ensures that all organic matter is oxidized.

- Phosphate Removal: Use a phosphate test kit. If levels exceed 200 ppb, add a lanthanum-based phosphate remover. This will cause the water to cloud up as the phosphates precipitate, which will then need to be filtered out.

- Clarifiers: To assist the filter in catching the “moon dust” fines (PM2.5), add a polymer-based clarifier or flocculant. These chemicals act as coagulants, clumping the fine dust into larger particles that the filter can trap.

Section 4: Long-Term Prevention Strategies

In the Queen Creek and San Tan Valley region, haboobs are a cyclical inevitability. Relying solely on reactive maintenance is a recipe for equipment fatigue and exorbitant repair costs. A resilient pool system requires a defensive strategy focused on exclusion (keeping dust out) and hardening (protecting equipment).

Equipment Protection and Hardening

The equipment pad is the nerve center of the pool, yet it is often left exposed to the full brunt of the elements.

- Ventilated Pump Covers: The sun in Arizona is as damaging as the dust. Installing ventilated motor covers protects the pump from direct UV radiation, which degrades plastic housings and capacitors, while also shielding the motor vents from direct dust intrusion. A cooler motor runs more efficiently and has a longer lifespan.

- Surge Protection: Haboobs are often accompanied by lightning and grid fluctuations. The installation of a dedicated surge protector at the pool sub-panel can save variable-speed drive (VSD) pumps, which are highly sensitive to voltage spikes, from frying during a storm.

- Walled Enclosures: Constructing a three-sided masonry wall around the equipment pad (with proper ventilation gaps) acts as a physical barrier against wind-driven sand, reducing the abrasive scouring of pipes and valve handles.

Wind Barriers and Agronomic Landscaping

Modifying the aerodynamics of the backyard environment can significantly reduce the particulate load that reaches the water.

- Wind Fencing: Solid walls often create turbulence that deposits dust on the leeward side—right into the pool. Porous windbreaks, such as mesh windscreens or louvered fences that allow ~50% airflow, are aerodynamically superior. They reduce wind velocity by up to 75% without creating turbulence, causing the heavy dust load to drop out of the air stream before it reaches the pool surface.

- Botanical Shields: Selecting the right vegetation is critical. The goal is to plant trees that act as wind filters without generating their own litter.

- Recommended Species: The Arizona Cypress (Cupressus arizonica) and Pygmy Date Palm (Phoenix roebelenii) are excellent choices for Queen Creek. They have dense foliage that traps dust but do not shed excessive leaves or flowers. The Ficus Nitida (Indian Laurel) is heavily used as a dense hedge to block wind and noise.

- Species to Avoid: Mesquites (unless low-litter hybrids), Cottonwoods, and deciduous varieties that drop leaves during the monsoon season should be avoided near the pool.

Pool Covers: The First Line of Defense

- Solid Safety Covers: These provide the highest level of protection, blocking 99% of dust and sunlight (preventing algae). However, they require effort to deploy. Anchoring systems must be robust (e.g., brass anchors in concrete) to withstand 60 mph winds without lifting.

- Automatic Covers: While a significant capital investment, automatic covers can be deployed in under 60 seconds when a storm warning is issued. They are the most effective tool for keeping a pool clean. Crucial Operational Note: After a storm, the dust will be sitting on top of the cover. This must be removed (pumped or swept) away from the pool before the cover is opened, otherwise, the accumulated load will dump directly into the water, negating the protection.

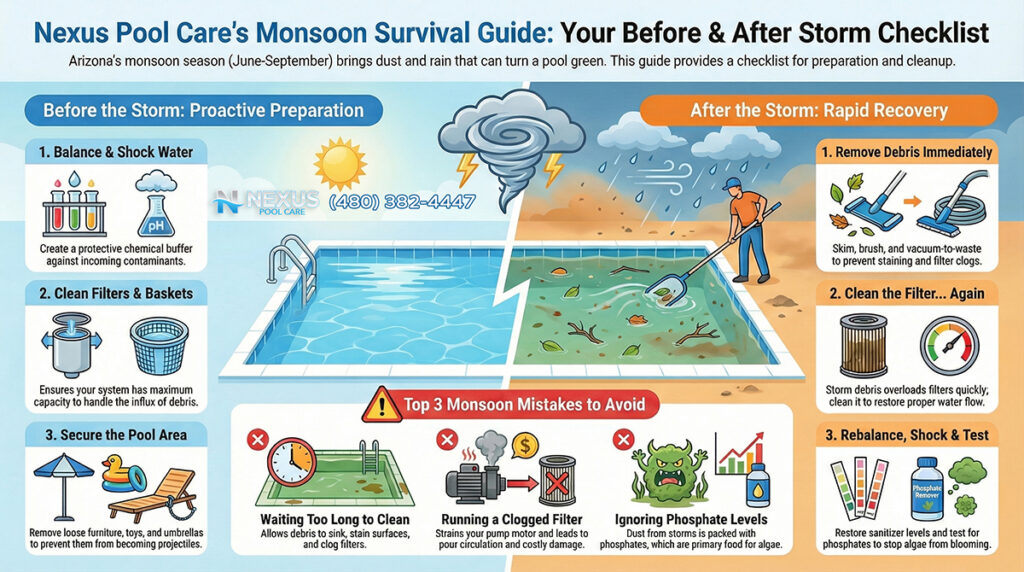

Adjusted Maintenance Schedules

The “set it and forget it” mentality does not work in monsoon country. Maintenance routines must adapt to the season.

- Seasonal Filter Cleaning: In Queen Creek, filter cleaning intervals should accelerate during the summer. Instead of the standard bi-annual clean, filters should be cleaned quarterly, with specific attention paid in June (pre-monsoon) and October (post-monsoon).

- Pre-Storm Protocols: When a haboob warning is issued:

- Overfill the Pool: Add 2 inches of water to account for the water loss that will occur during the post-storm “vacuum to waste” process.

- Boost Chlorine: Add a preventative shock dose to establish a high sanitizer residual before the organic load hits.

- Secure the Area: Remove floats, umbrellas, and lightweight furniture that can become projectiles and damage the pool finish or equipment.

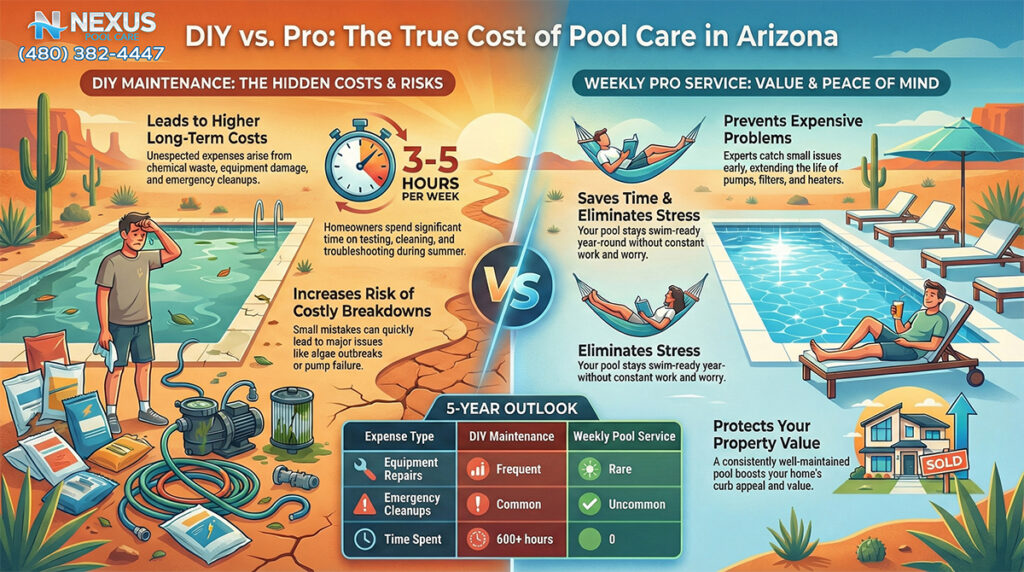

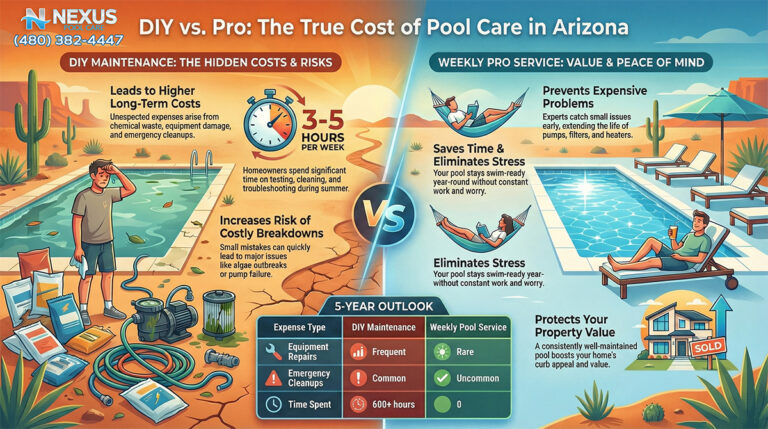

The Bottom Line: Proactive Care Extends Equipment Life

The haboob is an unavoidable reality of the Sonoran Desert ecosystem. For pool owners in Queen Creek, it represents a violent convergence of geological and meteorological forces that stress aquatic engineering to its breaking point. The difference between a minor cleanup event and a catastrophic equipment failure lies in the understanding of the system’s vulnerabilities.

Key Takeaways for the Queen Creek Pool Owner:

- The Dust is Chemical: Treat the dust not just as dirt, but as a phosphate-laden fertilizer that demands immediate chemical neutralization to prevent uncontrollable algae blooms.

- Vacuum to Waste is Non-Negotiable: Pushing haboob sludge through a cartridge filter is a death sentence for the media. Investment in a trash pump or plumbing modification to allow bypass is essential for single-cartridge systems.

- Heat + Dust = Failure: The synergistic effect of restricted airflow (dust) and high ambient temperature (110°F) kills pumps. Keeping equipment clean, ventilated, and shaded is as important as keeping the water clear.

- No Shortcuts: Draining a pool to clean it risks structural failure due to hydrostatic pressure. Acid washing a filter before degreasing it ruins the cartridge. The protocols outlined here—skim, waste-vac, chemical balance, filter clean—must be followed in strict sequence.

By adopting a defensive posture—utilizing windbreaks, proper covers, and preemptive maintenance—pool owners can transform the haboob from a disaster into a manageable maintenance event, ensuring their filtration systems survive the storm to run another day.

Detailed Data Appendices

Appendix A: Filter Type Performance Under Haboob Conditions

| Filter Type | Filtration Rating (Microns) | Haboob Resilience | Main Vulnerability | Post-Storm Recovery | Queen Creek Suitability |

| D.E. (Diatomaceous Earth) | 2 – 5 (Best) | Low | Grids clog (“bridge”) rapidly with fine silt; requires immediate backwash/teardown. | High Labor: Disassembly, cleaning, and recharging required. | High Performance / High Maintenance – Best water clarity but requires work. |

| Cartridge | 10 – 20 (Good) | Medium | Pleats can be crushed by high pressure; mud can cement into fabric if not cleaned wet. | Moderate Labor: Remove cartridges, hose, and soak (TSP). No backwashing. | Standard – Most common, but requires “Vacuum to Waste” bypass to survive storms. |

| Sand | 20 – 40 (Fair) | High | Sand bed resists clogging but allows fine dust to pass through (cloudy water). | Low Labor: Simple backwash. May require flocculants to clear fines. | Robust / Low Clarity – Hard to kill, but struggles to polish water crystal clear after dust. |

Appendix B: Pump Lifespan Reduction in Arizona

| Environmental Stressor | Impact Mechanism | National Avg Lifespan | Arizona Avg Lifespan | Mitigation Strategy |

| Silica Dust (Abrasive) | Erodes impeller vanes; scours pump volute; creates seal leak paths. | 8 – 12 Years | 5 – 7 Years | Install wind barriers; clean skimmer baskets daily; use pump covers. |

| Ambient Heat (110°F+) | Degrades capacitors; dries out lubrication; overheats motor windings. | 8 – 12 Years | 5 – 7 Years | Ensure ventilation; run pumps at night; use motor shades/covers. |

| Hard Water (Calcium) | Scale buildup on heat sinks and impellers; cements debris in filters. | 8 – 12 Years | 5 – 7 Years | Monitor Calcium Hardness (200-400 ppm); use sequestering agents. |

Appendix C: Post-Storm Chemistry Rebalancing Guide

| Parameter | Impact of Haboob/Rain | Target Level | Adjustment Chemical | Risk of Neglect |

| Free Chlorine | Rapid Drop (0 ppm) due to organic demand. | 3 – 5 ppm | Liquid Chlorine / Cal-Hypo Shock | Immediate algae bloom (green pool within 24-48 hrs). |

| Phosphates | Massive Spike (>1000 ppb) from dust/fertilizer. | < 100 ppb | Phosphate Remover (Lanthanum) | Fuel for algae that resists chlorine; constant green pool. |

| pH | Fluctuates (Rain=Acidic, Dust=Alkaline). | 7.4 – 7.6 | Muriatic Acid (Lower) / Soda Ash (Raise) | Scaling (high pH) or Corrosion (low pH); eye irritation. |

| Filter Pressure | Spike (>10 PSI over clean). | Baseline | Filter Clean / Backwash | Crushed cartridges; reduced circulation; pump burnout. |