Introduction: The Hidden Toll of 110°+ Arizona Summers on Pool Systems

Table of Contents

ToggleThe operational environment of the American Southwest, particularly the low desert regions of Arizona, presents a unique and hostile challenge to the longevity of mechanical and electrical infrastructure. While swimming pool equipment—comprising filtration pumps, heating units, sanitation devices, and automation controls—is nominally rated for outdoor use, the “outdoor” conditions assumed by manufacturers typically align with temperate climates, capping ambient design temperatures at approximately 40°C (104°F). In contrast, the Arizona summer frequently imposes ambient air temperatures exceeding 43°C (110°F), coupled with intense solar insolation that can elevate surface temperatures of dark-colored equipment to over 70°C (160°F).

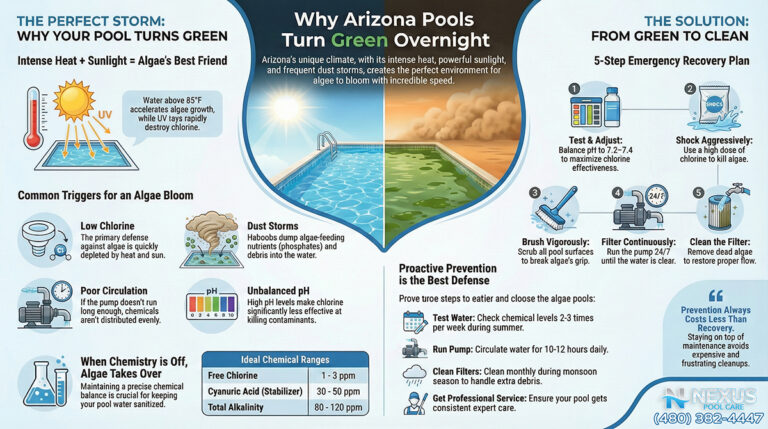

This thermal excess acts not merely as a temporary environmental stressor but as a relentless accelerant of entropy. The degradation of pool systems in this region is rarely the result of a single catastrophic event; rather, it is the cumulative consequence of operating mechanical systems at the very edge of, or beyond, their thermodynamic design envelopes. The phenomenon is best understood through the lens of the Arrhenius equation, a fundamental principle of physical chemistry which dictates that the rate of chemical reaction—and by extension, material degradation—approximately doubles for every 10°C rise in temperature. In the context of the Arizona equipment pad, this exponential relationship implies that a pump motor or chlorinator cell operating in the blazing Phoenix sun may experience aging rates four to eight times higher than an identical unit operating in a shaded, ventilated environment in a temperate climate like the Pacific Northwest.

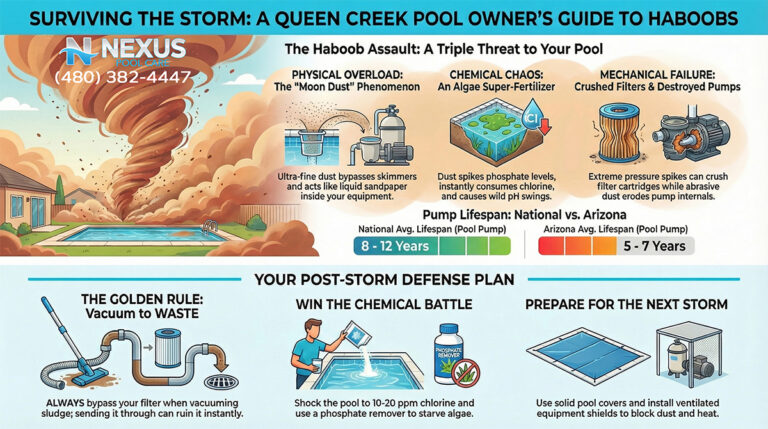

The “hidden toll” manifests as a drastic reduction in the Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) and the overall service life of critical components. Industry data indicates that pool pumps in Arizona have an average lifespan of only 5 to 7 years, a stark contrast to the national average of 8 to 12 years.6 This reduction is driven by a triad of environmental aggressors distinct to the region: extreme thermal cycling, intense ultraviolet (UV) radiation, and the abrasive, chemically reactive nature of hard water and dust.

The equipment pad, often a concrete slab, exacerbates these conditions. Concrete possesses high thermal mass and conductivity, absorbing solar radiation throughout the day and reradiating it into the equipment long after sunset. This creates a localized microclimate where the temperature remains critically high even at night, denying motors and electronics the cooling period they rely on to reach thermal equilibrium.3 Consequently, the “Arizona Factor” transforms standard pool maintenance from a routine of cleaning and chemistry into a rigorous exercise in thermal management and preventative engineering. Understanding the physics of these failures is the first step toward mitigating the substantial financial and operational risks faced by pool owners in hyper-arid climates.

Section 1: How Heat Damages Pool Equipment

The degradation of aquatic support systems in extreme heat is driven by three primary mechanisms: the tribological breakdown of seals and lubricants, the thermal-electrical failure of motor insulation and capacitors, and the photo-oxidative decomposition of structural polymers. These mechanisms often operate synergistically; for instance, a seal hardened by heat may allow moisture ingress, which then causes a short circuit in a motor winding already weakened by thermal stress.

1.1 Seal Failure: The Thermodynamics of Elastomer Degradation

Elastomeric seals—O-rings, shaft seals, and gaskets—are the sentinels of the pool system, maintaining hydraulic integrity under constant pressure. In the extreme heat of an Arizona summer, these components are subject to accelerated aging processes that compromise their elasticity and sealing capability.

Compression Set and Cross-Linking

The primary failure mode for static seals (O-rings) in high-temperature environments is “compression set.” Elastomers function by being compressed between two rigid surfaces, generating a restoring force that creates a barrier to fluid passage. However, at elevated temperatures, the polymer chains within the rubber undergo additional, uncontrolled cross-linking. This post-vulcanization process increases the material’s hardness and reduces its ability to rebound. When the seal is held in a compressed state at high temperatures—such as an O-ring inside a hot filter tank clamp—the polymer chains realign to the compressed shape.

When the system eventually cools, typically during the diurnal cycle or when the pump cycles off, the metal or plastic housing contracts. A healthy seal would expand to maintain contact, but a heat-damaged seal with high compression set stays flattened. This loss of “elastic memory” creates a gap, resulting in a leak. In Arizona, where daily temperature swings can be significant, this thermal cycling puts immense mechanical stress on seals, causing them to fail far earlier than their rated lifespan.

Material-Specific Thermal Vulnerabilities

The rate and severity of seal failure are heavily dependent on the material composition of the elastomer.

| Elastomer Type | Temperature Ceiling | Failure Characteristics in Extreme Heat | Arizona Context |

| Nitrile (Buna-N) | ~120°C (250°F) | Hardening, surface cracking, loss of tensile strength. |

Standard in most residential equipment; prone to rapid failure in direct sun due to high surface absorption temperatures.9 |

| EPDM | ~150°C (300°F) | Sooty surface degradation, embrittlement when combined with high chlorine. |

Better heat resistance than Nitrile but susceptible to chemical attack, which is accelerated by heat.9 |

| Viton (FKM) | ~200°C (400°F) | Generally robust, but can suffer from chemical degradation if pH is unregulated. |

Superior choice for high-heat applications but more expensive; less common in standard kits.11 |

| Silicone | ~230°C (450°F) | Poor tear strength; typically used only for static gaskets, not dynamic seals. |

Excellent heat resistance but mechanically weaker; rarely used for high-pressure pump seals.11 |

Tribological Failure in Dynamic Seals

The mechanical shaft seal, which isolates the wet end of the pump from the dry motor, relies on a microscopic fluid film to lubricate the interface between a stationary seat (usually ceramic) and a rotating face (usually carbon). In extreme heat, the water in the pump housing can approach its boiling point, particularly if flow is restricted by a dirty basket—a common occurrence during Arizona’s monsoon season.13

As the fluid temperature rises, its viscosity decreases and its vapor pressure increases. This can lead to “flashing,” where the fluid film vaporizes at the seal interface. The seal then runs dry, generating intense frictional heat that can thermally shock the ceramic face, causing it to crack, or cause the carbon face to pit and blister.3 Once the seal faces are damaged, water sprays onto the motor shaft, migrating along it to attack the front bearing, initiating a cascade of mechanical failures.14

1.2 Motor Overheating: Dielectric Breakdown and Bearing Failure

Electric motors are thermodynamic devices that generate heat as an unavoidable byproduct of converting electrical energy into mechanical work. They rely entirely on the transfer of this waste heat to the surrounding environment to remain within safe operating limits. In Arizona, where the “cooling” air can be 45°C (113°F) or higher, the thermal gradient required for effective heat dissipation is severely compromised.

The 10°C Rule and Insulation Classes

Motor windings are insulated with a varnish or enamel coating, classified by their thermal endurance (e.g., Class B for 130°C, Class F for 155°C). The internal temperature of the motor is the sum of the ambient temperature plus the temperature rise caused by the electrical load. If an improperly ventilated or sun-exposed motor operates at a temperature just 10°C above its rated insulation class, the useful life of that insulation is cut in half.

For a motor rated for a 40°C ambient environment, operating in 50°C air (common in direct sun) without factoring in the additional heat rise from the load puts it immediately in a danger zone. Over time, the thermal stress causes the insulation to become brittle and crack. This eventually leads to an inter-turn short circuit, where the electrical current bypasses the windings, causing a catastrophic “burnout” that necessitates complete motor replacement.

Capacitor Failure: The Mechanism of Electrolytic Evaporation

Single-phase pool pumps utilize run capacitors to create a rotating magnetic field essential for torque generation. These components typically utilize a liquid electrolyte within a metal or plastic housing. The electrolyte is volatile, and its evaporation rate is directly linked to temperature.

High ambient heat, combined with the internal heating of the capacitor during operation, increases the internal pressure and accelerates the diffusion of electrolyte vapor through the seals. As the electrolyte volume diminishes, the capacitance (measured in microfarads, µF) drops, and the Equivalent Series Resistance (ESR) rises.

This creates a destructive feedback loop: higher resistance generates more internal heat, which drives further evaporation.

-

Humming vs. Buzzing: A failing capacitor often manifests as a motor that “hums” but will not start. The hum is the sound of the stator coils being energized but unable to generate the phase shift required to turn the rotor. This locked-rotor condition causes a massive spike in current and heat, which can cook the windings in a matter of minutes if the thermal overload switch fails to trip.

-

Physical Signs: A capacitor that has failed due to heat often exhibits a bulging top or bottom, a result of the internal pressure buildup from the vaporized electrolyte.

Bearing Grease Degradation

Sealed ball bearings are pre-packed with a specific volume of grease, which consists of a base oil held in a thickener (soap). High temperatures cause the base oil to decrease in viscosity and “bleed” out of the thickener. Once the oil is lost, the bearing runs on the dry thickener and metal, leading to rapid wear, high friction, and extreme heat generation. This failure is audible as a loud screeching or grinding noise, a ubiquitous sound in Arizona neighborhoods during the summer.

1.3 Plastic Component Breakdown: UV and Thermal Degradation

The majority of modern pool equipment housings are manufactured from thermoplastics such as Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), Polypropylene (PP), or Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS). While often reinforced with glass fibers and UV stabilizers, these materials are fundamentally organic polymers susceptible to the high-energy photons of the sun.

Photo-Oxidation and the “Chalking” Phenomenon

Ultraviolet radiation, specifically UV-B, possesses sufficient energy to break the covalent bonds within the polymer backbone, a process known as chain scission. In PVC, this leads to dehydrochlorination, where chlorine atoms are stripped from the carbon chain. The visible result is “chalking”—the formation of a white, powdery layer on the surface of the equipment.

This powder is comprised of titanium dioxide (TiO2), a pigment used to protect the plastic, which is released as the polymer matrix erodes around it.20 While this layer can protect the underlying material to some extent, it signals that the outer surface has lost its structural integrity.

Impact Strength vs. Tensile Strength

Crucially, UV degradation affects the mechanical properties of plastics unevenly. Research indicates that while the tensile strength (resistance to being pulled apart) of PVC may remain relatively stable after years of sun exposure, the impact strength (resistance to sudden shock) drops precipitously. A filter tank that has baked in the Arizona sun for five years might still hold pressure (tensile load) but could shatter catastrophically if struck by a tool or subjected to a water hammer event.

Thermal Creep

Thermoplastics soften as temperature increases. At surface temperatures of 140°F—easily achievable on dark equipment housings in the sun—the modulus of elasticity drops, making the material more ductile. Under constant internal pressure (such as in a filter tank or chlorinator cell), the housing can undergo “creep,” a slow, permanent deformation. This can warp sealing surfaces, causing lids to stick or O-ring grooves to become oval, leading to persistent, unfixable leaks.

Section 2: Most Vulnerable Pool Components

While the entire equipment pad faces the same environmental assault, the vulnerability of individual components varies based on their construction, function, and location within the hydraulic loop. Understanding these specific vulnerabilities allows for more targeted inspection and protection strategies.

2.1 Pumps: The Kinetic Heart

The circulation pump is the most stressed component of the pool system, burdened with both internal heat generation from the motor and external heat load from the environment. It is the component most likely to fail first in a hyper-arid climate.

-

Vulnerability Profile: Critical / High.

-

Primary Failure Mode: Motor winding burnout and bearing seizure.

-

Mechanism of Failure:

-

Cavitation in Hot Water: As water temperature rises, the Net Positive Suction Head Available (NPSHa) decreases because the vapor pressure of the water increases. In Arizona, where pool water can reach 90-95°F, a minor restriction on the suction side (dirty basket, clogged cleaner) that would be benign in cooler water can cause the water to flash into vapor at the impeller eye. This cavitation acts like a sandblaster, pitting the impeller and sending shockwaves through the shaft that destroy bearings.

-

Seal Face Tribology: The “Arizona Factor” includes hard water scaling. As heat causes microscopic evaporation at the seal interface, calcium carbonate precipitates on the seal faces. These deposits are abrasive, grinding down the carbon face and causing leaks that destroy the motor.

-

2.2 Filters: The Pressurized Vessels

Pool filters (Cartridge, DE, and Sand) are large pressure vessels typically constructed from fiberglass-reinforced plastic or injection-molded polymers. Their large surface area makes them efficient absorbers of solar radiation.

-

Vulnerability Profile: Medium-High.

-

Primary Failure Mode: Structural degradation of the housing and internal manifold cracking.

-

Mechanism of Failure:

-

Fiber Bloom: On fiberglass tanks, intense UV exposure erodes the resin matrix, exposing the glass fibers. This “fiber bloom” creates a fuzzy, prickly surface. Exposed fibers wick moisture into the tank wall, leading to delamination and a reduction in the tank’s pressure rating.

-

Internal Fatigue: The internal manifolds and grids are made of plastics that soften in heat. Subjected to the cyclic loading of the pump turning on and off, these softened internal parts fatigue and crack. A cracked manifold allows dirt to bypass the filter, returning to the pool and clouding the water.

-

Safety Hazard: A chemically and thermally degraded filter tank represents a significant safety risk. The stored potential energy in a pressurized vessel can cause an explosive rupture if the material properties are compromised.3

-

2.3 Heaters: The Thermal Paradox

Pool heaters, particularly gas-fired units, present a paradox: they are designed to generate intense heat, yet they are remarkably sensitive to environmental heat and water chemistry anomalies driven by high temperatures.

-

Vulnerability Profile: High.

-

Primary Failure Mode: Heat exchanger scaling and electronic control failure.

-

Mechanism of Failure:

-

Inverse Solubility Scaling: Arizona water is characteristically hard, with high levels of calcium hardness (often 250+ ppm). Calcium carbonate exhibits inverse solubility, meaning it becomes less soluble as water temperature rises. Inside the heat exchanger, where water contacts copper tubes heated by gas flames, the local temperature is highest. This causes rapid precipitation of calcium scale on the copper surfaces.

-

The Insulator Effect: This scale acts as an insulator, trapping heat within the copper metal rather than transferring it to the water. The copper tubes then overheat, leading to thermal stress cracking, melting of the finned tubes, or “kettling” (a banging noise caused by boiling water inside the exchanger).

-

Electronic Embrittlement: Modern heaters utilize sophisticated digital control boards located under a plastic bezel, typically on the top of the unit—the area most exposed to the sun. The ambient heat inside the cabinet, combined with solar gain, can exceed the thermal rating of the electronic components (capacitors, solder joints), leading to board failure.

-

2.4 Automation and Salt Systems

Automation centers and salt chlorinators rely on sensitive electronics housed in outdoor enclosures. While these enclosures are NEMA-rated for rain, they are often ill-equipped to handle the thermal load of the desert.

-

Vulnerability Profile: Medium.

-

Primary Failure Mode: LCD screen failure and power supply overheating.

-

Mechanism of Failure:

-

LCD Delamination: Liquid Crystal Displays consist of organic fluid sandwiched between glass and polarizing filters. High heat can cause the liquid crystal fluid to change phase or the polarizing layers to delaminate. This results in the screen turning completely black or unreadable—a ubiquitous issue for Arizona controllers facing the sun.

-

Salt Cell Degradation: The potting material that seals the electrical connections on the salt cell can degrade and crack in high heat, allowing moisture intrusion and short circuits. Additionally, the power centers for these units contain transformers and rectifiers that generate significant waste heat; adding solar load to this can cause frequent thermal shutdowns.

-

2.5 Plumbing and PVC Infrastructure

The network of PVC pipes and valves is the skeletal system of the pool, often overlooked until a failure occurs.

-

Vulnerability Profile: Low-Medium.

-

Primary Failure Mode: Joint failure and impact shattering.

-

Mechanism of Failure:

-

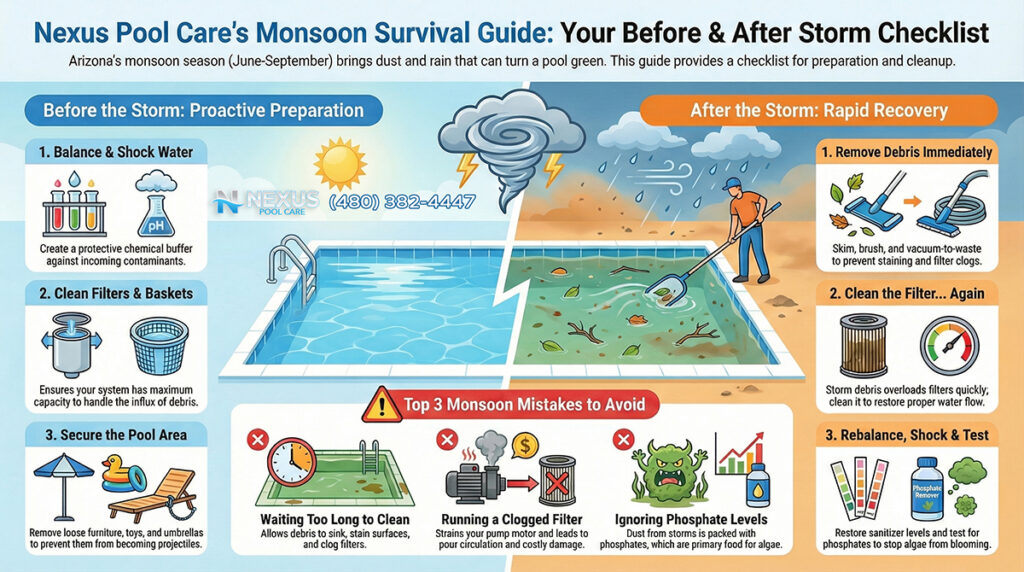

Creep at Glue Joints: Standard Schedule 40 PVC has a maximum operating temperature of 60°C (140°F). While circulating pool water rarely reaches this, stagnant water trapped in pipes exposed to direct sun can easily exceed it. This thermal cycling causes “creep” at the solvent-welded joints, leading to slow leaks, particularly on the pressure side of the pump.

-

Valve Seizure: Diverter valves rely on internal O-rings and lubricated seals. In extreme heat, the lubricant dries out and the O-rings swell (compression set), making the valves difficult or impossible to turn without breaking the handle.

-

Section 3: How to Protect Equipment from Heat Damage

Mitigating the destructive effects of the Arizona climate requires a defense-in-depth approach. It is insufficient to rely on the equipment’s inherent ruggedness; owners must actively engineer the environment to decouple the equipment from thermal stressors.

3.1 Shade Structures: The First Line of Defense

Direct solar radiation is the single largest contributor to premature equipment aging in Arizona. Blocking the sun can reduce the surface temperature of equipment by 10°C to 20°C (20-40°F), keeping materials well below their glass transition temperatures and preventing UV degradation.

Ventilated Enclosures vs. Sheds

A common mistake is enclosing equipment in a small, non-ventilated shed. In the desert, this creates a “greenhouse effect,” trapping motor heat and raising the internal temperature to dangerous levels.

-

Design Requirement: The ideal structure blocks direct UV rays and rain while allowing unrestricted airflow. It should have a solid or shaded roof but open or louvered sides.

-

The “Chimney Effect”: Designing the structure with openings at the bottom and top encourages natural convection, where hot air rises out of the top vents, drawing cooler air in from the bottom.

Material Selection for Shade

-

Alcan/Aluminum Covers: Highly effective at reflecting solar radiation. They are durable and do not degrade under UV, making them a long-term solution.

-

Shade Sails (HDPE Mesh): High-density polyethylene mesh fabric is excellent for Arizona. It blocks 90-95% of UV rays but is porous, allowing hot air to rise through the fabric rather than trapping it. This prevents the formation of a heat pocket underneath the shade. It is often the most cost-effective and aesthetically pleasing solution for residential pools.

Strategic Orientation

For new installations or movable structures, orientation is key. In the Northern Hemisphere, the southern and western exposures are the most intense. Equipment pads should ideally be located on the north side of the home. If this is impossible, a shade structure should be positioned specifically to block the low-angle late afternoon sun (western exposure), which is the hottest part of the day.

3.2 Proper Ventilation and Airflow Management

Motors are air-cooled devices. If the airflow is restricted, the motor will overheat regardless of the ambient temperature or shade.

-

Clearance Zones: Industry best practices and codes suggest maintaining a minimum of 3 feet of clearance around the equipment pad. Overgrown vegetation is a common culprit; dense bushes like oleanders or bougainvillea can choke off airflow and increase local humidity, which retards cooling.

-

ASHRAE Standards: For enclosed pump rooms, passive vents are often insufficient in Arizona. Thermostatically controlled exhaust fans are required. The design standard is to change the air in the room 4 to 6 times per hour to prevent heat buildup.

-

Pad Elevation: Equipment should be mounted on a concrete pad raised above the surrounding grade. This prevents flooding during monsoons and allows for better air circulation around the base of the motor.

3.3 Optimized Pump Runtimes and Variable Speed Technology

Operational adjustments can significantly reduce thermal stress without requiring capital improvements.

Thermodynamics of Nighttime Operations

Running the filtration cycle at night (e.g., 8 PM to 6 AM) takes advantage of the diurnal temperature swing. The ambient air is cooler, allowing the motor to dissipate heat more efficiently. Additionally, electricity rates are typically lower during these off-peak hours, providing a financial incentive.

Variable Speed Pumps (VSPs): The Thermal “Silver Bullet”

VSPs are the most effective technological solution for heat management.

-

Affinity Laws: Pump affinity laws state that power consumption drops by the cube of the speed reduction. A pump running at half speed consumes 1/8th the power.

-

Thermal Benefit: Less power consumption means significantly less waste heat generation. A TEFC (Totally Enclosed Fan Cooled) motor on a VSP running at low RPM generates a fraction of the heat of a single-speed induction motor. It runs cooler, quieter, and vibrates less, significantly extending the life of bearings and seals.

3.4 Routine Inspections and Preventative Maintenance

In a harsh climate, maintenance must be proactive rather than reactive. The goal is to identify stress indicators before they cascade into failure.

The “Touch Test” and Sensory Inspection

-

Thermal: Place a hand on the motor body during operation. It should be warm to the touch (approx. 50-60°C), but not so hot that you must immediately pull your hand away. If it is scorching, this indicates bearing failure, winding issues, or obstructed ventilation.

-

Auditory: Listen for changes in pitch. A high-pitched “screech” indicates dry bearings. A low “hum” without rotation indicates a seized impeller or failed capacitor.

-

Visual: Look for the “weep.” A mechanical seal often leaks a small amount of water before catastrophic failure. Look for white calcification marks on the concrete pad directly under the pump. Addressing this immediately prevents water from entering the motor bearings.

Capacitor Prophylaxis

The run capacitor is a consumable item in the desert. Proactive replacement every 2-3 years, regardless of apparent function, is a cheap insurance policy (approx. $20 part) against motor burnout. Capacitors should be tested annually with a multimeter to ensure they are within +/- 5% of their rated microfarad value.

Chemical Management for Heat

-

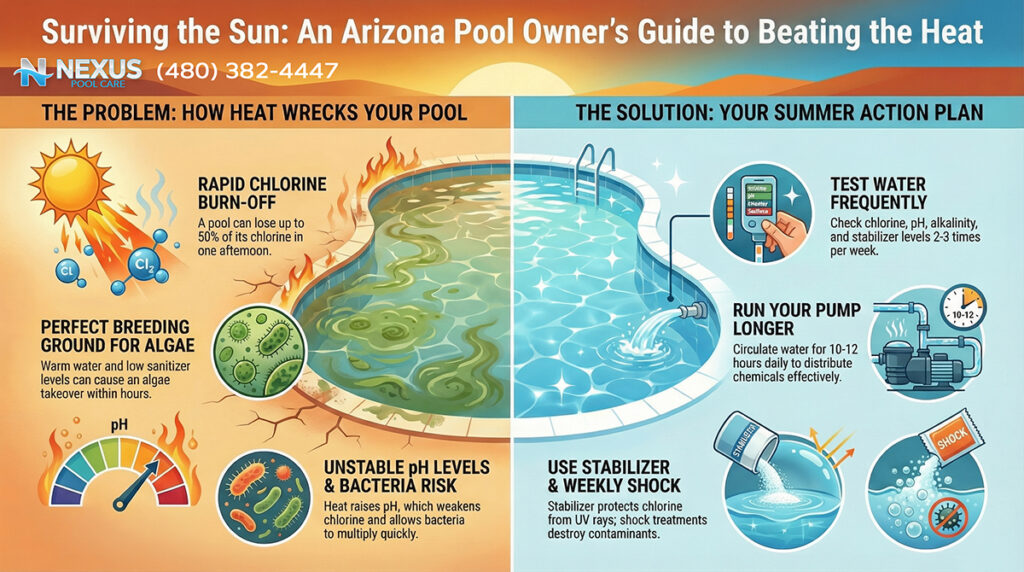

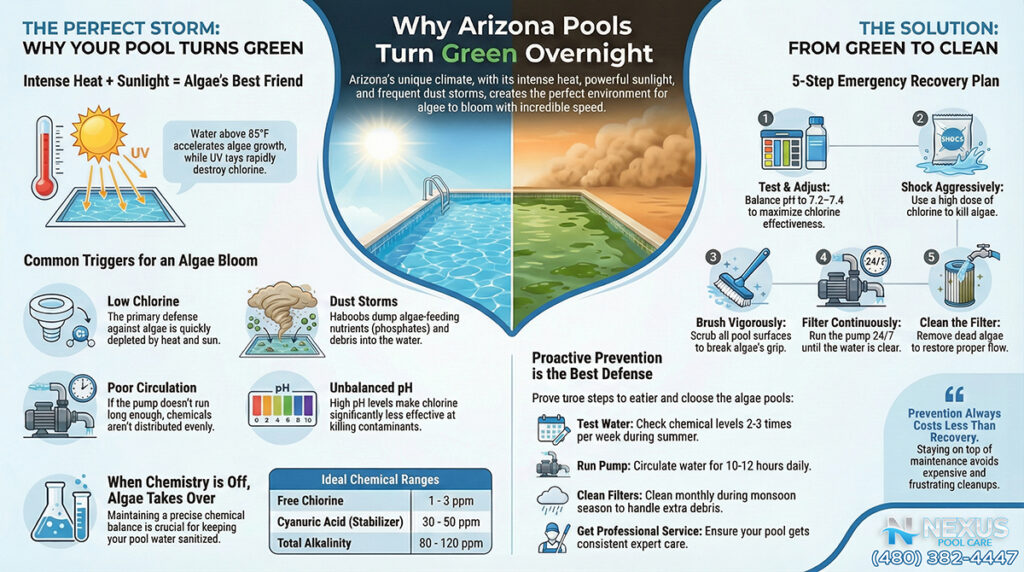

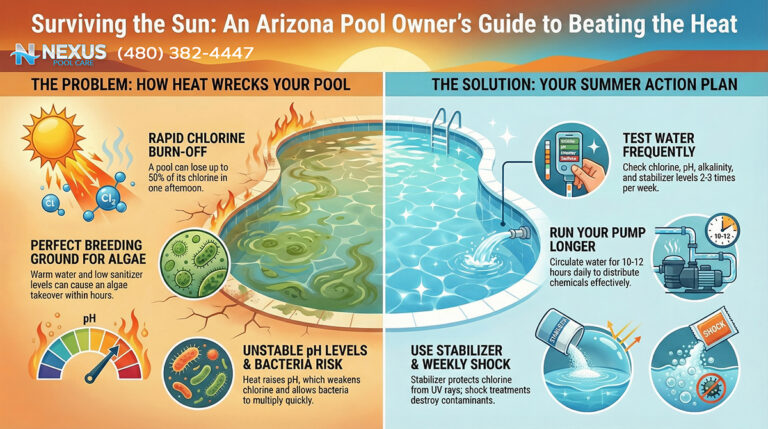

Chlorine Demand: Heat accelerates the degradation of chlorine. In summer, stabilizers (Cyanuric Acid) must be maintained at optimal levels (30-50 ppm) to protect chlorine from UV, but not so high that they lock up the chlorine’s effectiveness.

-

LSI Management: The Langelier Saturation Index (LSI) is temperature-dependent. As water heats up, it becomes more scale-forming. To protect heaters and salt cells, the pH and alkalinity may need to be kept slightly lower in the summer to maintain a balanced LSI and prevent scale deposition.

Section 4: When to Repair vs Replace Pool Equipment

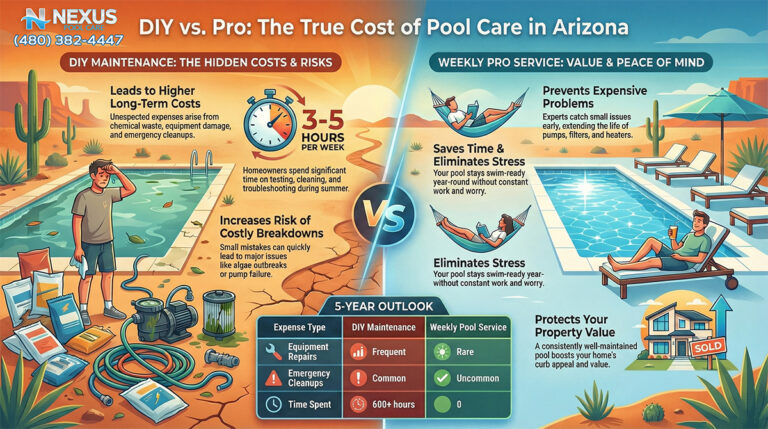

The decision to repair or replace equipment in Arizona is complicated by the accelerated aging process. A 5-year-old pump in Phoenix may have the internal wear equivalent to a 10-year-old pump in a cooler climate. The traditional models of depreciation must be adjusted for the “desert dog years” factor.

4.1 The Decision Matrix: Age and Cost

A rational decision framework involves analyzing the age of the equipment, the cost of the repair, and the efficiency gains of replacement.

2025 Arizona Repair vs. Replace Cost Guide

The following table synthesizes current data on repair and replacement costs in the Arizona market.

| Component | Average AZ Lifespan | Typical Repair Costs | Replacement Cost (Est.) | Decision Rule of Thumb |

| Single Speed Pump | 5-7 Years | $150 – $400 (Motor/Seal) | $700 – $1,500 | Replace if > 5 years old or if repair > 40% of new cost. |

| Variable Speed Pump | 8-10 Years | $350 – $650 (Drive/Motor) | $1,500 – $2,500 | Repair if < 6 years old. Replace if drive failure is out of warranty. |

| Filter (Tank) | 10-15 Years | $100 – $300 (Grids/Cartridges) | $300 – $1,000+ | Never repair a cracked tank. Replace immediately for safety. |

| Gas Heater | 5-10 Years | $200 – $500 (Switches/Board) | $1,500 – $3,500+ | Replace if heat exchanger is leaking or rusted. Repair minor electrical only. |

| Salt Cell | 3-5 Years | N/A (Cleaning only) | $600 – $1,200 | Replace when cell fails to hold amperage or plates are eroded. |

The Modified 50% Rule

A standard industry guideline is the “50% Rule”: if the repair cost equals or exceeds 50% of the cost of a new unit, replace it. In Arizona, this threshold should arguably be lowered to 40% for equipment over 5 years old. The probability of secondary failures (e.g., a plastic housing cracking shortly after a motor replacement) is high due to heat embrittlement.

4.2 Warning Signs of Imminent Failure

Recognizing the early warning signs can prevent emergency replacements during the peak of summer when service companies are booked weeks out.

-

Auditory Cues:

-

Screeching/Grinding: Indicates bearing failure. Immediate action is required to save the motor core.

-

Kettling (Banging in Heater): Indicates heavy scale buildup or flow restriction in the heat exchanger. Continued operation will rupture the exchanger.

-

-

Visual Cues:

-

Chalky Residue on Plastics: Indicates advanced UV degradation. Do not pressure wash old filter tanks, as this strips the remaining resin.

-

Discolored/Faded LCDs: Indicates the screen has cooked in the sun. If the display is unreadable, control of the system is compromised.

-

Bulging Capacitors: Visible warping of the capacitor housing indicates internal pressure buildup and imminent failure.

-

-

Performance Cues:

-

Tripping Breakers: A pump that runs for 20-30 minutes and then trips the breaker is suffering from thermal breakdown of the windings. As the copper heats up, resistance changes, drawing more amps until the breaker trips.

-

4.3 Cost Considerations: The Efficiency Argument

The shift to Variable Speed Pumps (VSPs) is driven not just by regulation but by economic necessity in high-heat/high-use regions.

-

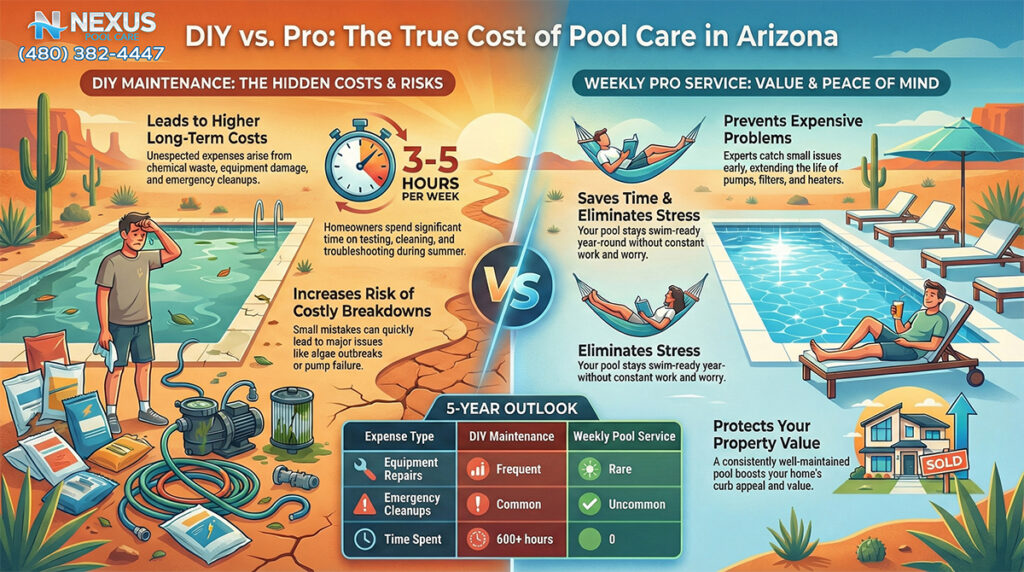

Energy ROI: Arizona pools often run year-round or have long summer runtimes (8-12 hours/day). A VSP can save $400–$800 annually in electricity compared to a single-speed pump. This savings can pay for the entire pump upgrade in 2-3 years.

-

Utility Rebates: Major Arizona utility providers (e.g., APS, SRP) frequently offer rebates for installing Energy Star-rated pool pumps, further offsetting the upfront cost and improving the Return on Investment (ROI).

The Bottom Line: Smart Protection Extends Equipment Life and Lowers Costs

The brutal Arizona summer does not have to be a death sentence for pool equipment. While the environment is undeniably hostile, the premature failure of pumps, filters, and heaters is largely a function of inadequate thermal management. The physics are clear: thermal expansion destroys seals, UV radiation unzips polymer chains, and Arrhenius kinetics cooks motor insulation.

However, these forces can be countered. Smart protection is a strategic investment that pays dividends in longevity and reliability. By installing simple shade structures, ensuring adequate ventilation, and utilizing variable speed technology, pool owners can effectively “derate” the environment, tricking the equipment into operating as if it were in a temperate climate.

Key Takeaways for the Arizona Pool Owner:

-

Shield it: Install ventilated shade structures (like shade sails) to block direct UV and reduce surface temperatures by up to 40°F.

-

Vent it: Ensure 3 feet of clearance and active ventilation for enclosed rooms; never stifle the motor’s need to breathe.

-

Time it: Shift heavy filtration cycles to the coolest part of the night to aid heat dissipation and save on energy.

-

Monitor it: Adopt a “touch and listen” inspection routine to catch bearing and capacitor failures before they destroy the motor.

Adopting these engineering controls transforms the pool system from a fragile, high-maintenance liability into a robust, durable asset capable of withstanding the harshest desert conditions. In the low desert, you cannot fight the heat, but with the right strategy, you can manage it.